A Short History of Belgian Chocolate

As far as chocolate's reach extends, it is still Brussels that sets the bar when in consumption

In 1915, Louise Agostini noticed that the delicate chocolates her husband had been making for the past three years were getting crushed inside the bags that were being used to package them. She developed a solution called the ballotin, a simple cardboard box that made sure their cargo remained intact, which quickly got noticed by other chocolate makers who adopted the design to protect their own sugary treats. Almost a century later, this container can be found stacked neatly on shelves across the globe, especially proliferate around Easter.

Around sixty years earlier, a man named Jean Neuhaus moved from Switzerland to , establishing an apothecary – a forerunner to the modern pharmacist – in a basement in the Galeries Royales Saint-Hubert. The local people quickly developed a penchant for Neuhaus’s remedies, which included liquorices, marshmallows and bars of dark chocolate, and the focus of his work consequently shifted from medicine to confectionary. The business grew, and was eventually passed along to Neuhaus’s son, Frédéric, and then his grandson, Jean Neuhaus II.

It was Neuhaus II who, in 1912, the year of his father’s death, succeeded in enveloping a soft fondant mixture within a hard chocolate shell, thus creating the world’s first ever praliné. It was an immediate success, and would find its way into the cavities of every sweet tooth in the world over the ensuing years, taking with it the tradition of Belgian chocolate making that was to become one of the country’s most celebrated exports over the course of the twentieth century.

Just one year after the praliné was unveiled, a man called Leonidas Kestekides settled in Brussels, having spent his formative years in Greece before moving to America in the late nineteenth century to make a living as a confectioner. He was outstanding at his craft, winning prestigious awards at the 1910 and 1913 World Fairs, and saw within Brussels the perfect environment in which to play his trade, not to mention a young lady to whom he promptly became married.

Twenty-three years later, his nephew pioneered the use of a guillotine-window through which to sell the company’s produce, a design not nearly as life-threatening as its name would suggest. It enabled customers to purchase and peruse as they walked by, rather than physically entering the shop, and was thus something of a harbinger of the drive-through window. Significantly, it brought Leonidas’s high quality chocolates a little closer to the masses, satisfying a dream held by the founder of the company which is today realised by the multitude of chocolate shops that can be found throughout Brussels.

In the Galeries Royales Saint-Hubert alone, for instance, there are four chocolate shops, including Neuhaus’s original outlet (which is still fully operational) and Godiva, established on the Grand Place by Joseph Draps in 1926, a little over a decade after Louise Agostini designed the first ballotin. The name of the company can be traced all the way to England’s West Midlands, where a lady called Godiva once took a novel approach to taxation protestation by riding through the streets of Coventry wearing not a single item of clothing. It was an act that earned her a reputation for being passionate, bold and pure, qualities which Draps also saw in his chocolates.

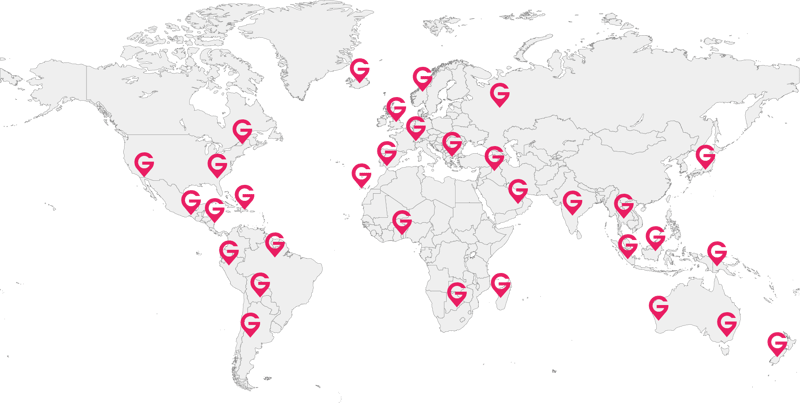

In 1958, Godiva began to expand beyond the borders of Belgium, a strategy that would see the company move first to Paris and then North America, establishing a global presence that means Godiva is now one of the most recognisable Belgian chocolatiers in the world. It is perhaps second only to a brand founded by Guy Forbert in 1960, which, over the past half century, has become globally ubiquitous, and is now a favourite gift amongst dinner party guests and last-minute Mother’s Day shoppers the world over.

Guy learnt his craft at the Antwerp School of Confectionery and Patisserie, where he began selling truffles at a local market before establishing Guylian. While it was he who had the idea of moulding each chocolate into the shape of a seashell and filling it with a hazelnut centre, it was his wife, Liliane, who pioneered the distinctive marbled veneer that makes each Guylian praliné instantly recognisable. The company now has the capacity to produce up to 75 tonnes of chocolate in a single day, an astonishing indication of the success it has achieved.

The story of these four companies presents a paradigm of Belgian chocolate’s journey, from its roots beneath the cobbled streets of Brussels to the shelves of shops around the world. Yet as far as its reach extends, it is still Brusseleers who set the bar when it comes to consumption. This is a city with one chocolatier for even 2,000 residents, where a single person eats 15 pounds of chocolate each year. It is this obsession with chocolate that ensures one of Belgium’s most beloved exports will remain so for years to come.

Image by EverJean